- CHESTERFIELD CULTURAL COUNCIL SEEKS FUNDING PROPOSALS

- Project Native Seasons End Plant Sale

- Massachusetts Agriculture in the Classroom 2010 Teacher of the Year: Cassandra Uricchio from Mount Everett High School

- Berkshire County Rx Round Up

- Campus to Congress to City Hall (C2C)

- FARMER MICROLOAN DEADLINE COMING SOON

- U.S. Meat Farmers Brace for Limits on Antibiotics

- ClearWater Conservancy: Restoration in Practice

- "A Bang for Your Buck in the Berkshires."

- How to shrink a city

CALENDAR OF EVENTS

Environmental Monitor

Public Notices Alphabeticallyby town

The BEAT News Archives

Advocacy News (Includes how to reach your legislators)

DEP Enforcement Actions In The Berkshire

return to top

CHESTERFIELD CULTURAL COUNCIL SEEKS FUNDING PROPOSALS

Proposals for community-oriented arts, humanities, and science projects due October 15.

The Chesterfield Cultural Council has set an October 15, 2010 postmark deadline for organizations, schools and individuals to apply for grants that support cultural activities in the community.

According to Council spokesperson Leslie Charles, these grants can support a variety of artistic projects and activities in Chesterfield — including exhibits, festivals, short-term artist residencies or performances in schools, workshops and lectures.

The Chesterfield Cultural Council will also entertain funding proposals from schools and youth groups through the PASS Program, which provides subsidies for school-age children to attend cultural field trips.

The Chesterfield Cultural Council is part of a network of 329 Local Cultural Councils serving all 351 cities and towns in the Commonwealth. The LCC Program is the largest grassroots cultural funding network in the nation, supporting thousands of community-based projects in the arts, sciences and humanities every year. The state legislature provides an annual appropriation to the Massachusetts Cultural Council, a state agency, which then allocates funds to each community. This year, the Chesterfield Cultural Council will distribute about $3870.00 in grants.

For specific guidelines and complete information on the Chesterfield Cultural Council, contact Leslie Charles (co-chair) at 413.296.4753 or [email protected]. Application forms and more information about the Local Cultural Council Program are available online at www.mass-culture.org/lcc_public.asp.

return to top

SEASON’S END SALE 10 – 50% OFF ALL PLANTS!

Up to 50% OFF ALL plants in stock for the remainder of the season.

Sale begins Thursday, September 23rd and continues through the end of the season!

Can not be combined with other offers or membership discounts.

Click here to check out Our NEW Website

return to top

Massachusetts Agriculture in the Classroom 2010 Teacher of the Year

MAC is proud to announce that our Teacher of the Year for 2010 is Cassandra Uricchio, who teaches agriculture and life science at Mount Everett High School in Sheffield.

Cassie participated in our 2007 Summer Graduate Course. She was awarded a mini-grant in 2008 to construct a school farm on campus. We have been inspired by her energy and passion for teaching agriculture and the many new programs she created.

The local Sheffield community also shares our enthusiasm for Cassie and her agricultural education efforts. We received nomination letters from the school’s principal; director of technology and vocational education; FFA president; the regional school district and the executive director of the Land Trust as well as a local farmer. All applauded her energy and drive and the connections she makes with her students, while also linking agriculture and the community.

After receiving a B.S. in Animal Science from UConn and a M.S. in Agricultural Education from NC State University, Cassie began teaching at Mt. Everett in 2006. She started a new agriscience program & FFA chapter in 2007. She developed new courses including Agricultural Biology; Agri-Science & Biotechnology; Animal Science, Plant Science; Pathobiology, and Fish & Wildlife Management. In the community she collaborated with the building structures program to raise a barn on school campus. Cassie is currently on leave of absence to return to NCSU on full assistantship to finish her Ed.D in Agricultural & Extension Education. We congratulate her and wish her the best in her studies.

The Autumn Spring edition of the Massachusetts Agriculture in the Classroom Newsletter is on the web at

http://www.umass.edu/umext/mac/Newsletters/Autumn%202010.htm

return to top

Berkshire County Rx Round Up

Saturday, September 25, 2010 10am – 2pm Berkshire County Locations

Do you have unused, unwanted or expired medications around your home? Help protect your family, community and the environment by safely disposing of them at the following locations:

North Berkshire County:

- Adams- Adams Police Station (4 School St.)

- Lanesborough- Berkshire Mall Food Court

- North Adams- Spitzer Senior Center (116 Ashland St.)

- Williamstown- Transfer Station (667 Simonds Rd./Rt.7)

Central Berkshire County:

- Dalton- Community Recreation Association (400 Main St.)

- Lee- Lee Ambulance (177 Main St.)

- Lenox- Lenox Commons (55 Pittsfield Rd.)

- Pittsfield- Berkshire United Way Parking Lot (200 South St.)

South Berkshire County:

- Egremont- Egremont Town Hall (171 Egremont Plain Rd.)

- Great Barrington- Police Station (465 Main Street)

- Sheffield- Sheffield Town Hall (21 Depot Square)

- Stockbridge- Police Station/Town Hall (50 Main St.)

ACCEPTED:

- Prescription Medications Over the Counter Medications Pet Medications Tablets/Pills/Capsules Patches

- Vitamins & Supplements Inhalers Suppositories Homeopathic Remedies Liquid Medications in Leak- Proof Containers

- Personal Use Needles/Sharps

NOT ACCEPTED:

IV Bags Blood or Infectious Waste Nebulizers Oxygen Tanks Mercury Thermometers

return to top

Campus to Congress to City Hall (C2C)

2010 Launch Conference – September 24th 3:30 p.m. to 9 p.m.

Center for Environmental Studies, Williams College

- C2C, an innovative grassroots network of faculty, students, staff and citizens committed to stopping global warming through clean energy solutions, will hold a launch conference on September 24th at Williams College.

- Economists Juliet Schor, author of Plenitude: the New Economics of True Wealth and Born To Buy: The Commercialized Child and the New Consumer Culture and Eban Goodstein, Director of Bard Center for Environmental Policy, will each give a keynote address.

- The conference will focus on growing this network involving a thousand universities and tens of thousands of students.

“Being a part of C2C is a great way for motivated students to talk directly with our nation’s decision makers about the importance of climate change.”

– Bard CEP Graduate Student, Rachel Savain

C2C is predicated on the belief that grassroots social movements drive social change in the US; only social movements have the power to overcome the natural gridlock of the US political system. From abolition to women’s suffrage, and from labor rights to civil rights, the power of a mobilized public has repeatedly swept through Washington, pushing through legislation that provided the foundation for subsequent decades of prosperity.

“Across the nation, at every college, university, high school and middle school, are dozens of faculty, students, and staff who understand that we are living at a truly extraordinary moment in history, and who are looking for a way to change the future. C2C is your network.”

– Eban Goodstein

Please join us September 24th from 3:30 p.m. to 9 p.m. at Williams College.

Event Schedule:

3:30-4:00 Registration, Harper House, coffee

4:00-5:30 Opening Remarks, Eban Goodstein, Director, Bard College Center for Environmental Policy, Thompson Biology 112

5:30-6:30 Breakout Climate Discussion Session #1, Thompson Biology 112, 202

6:30-7:00 Dinner (Pizza Provided)

7:00-8:00 Breakout Climate Discussion Session #2, Thompson Biology 112, 202

8:00-9:00 Keynote Speaker: Juliet Schor, Economist and Author of Plentitude: the New Economics of True Wealth and Born To Buy: The Commercialized Child and the New Consumer Culture, Thompson Biology 112

Registration is free and dinner will be provided.

To register: Kate Fletcher at [email protected]

For more information: Sarah Gardner at [email protected]

return to top

FARMER MICROLOAN DEADLINE COMING SOON

We are pleased to announce that the MassDevelopment/Strolling of the Heifers Small Farm Loan Program will be accepting prequalified applications through November 5, 2010 for loans of $15,000 or less. Applicants must live Massachusetts and prequalify. There are additional deadlines in January and March of 2011.

For more information, please go to www.thecarrotproject.org/farm_financing or contact Dorothy Suput at 617-666-9637 or at [email protected].

If you need the information in a different format, a copy of the application, or have any questions, please let me know.

Sincerely,

Dorothy Suput

Dorothy M. Suput

The Carrot Project

2 Belmont Terrace

Somerville, MA 02143

617-666-9637(p)

[email protected]

www.thecarrotproject.org

Sign-up for The Carrot Project’s periodic e-newsletter by sending a message to [email protected]

return to top

U.S. Meat Farmers Brace for Limits on Antibiotics

New York Times

On September 14th, the New York Times published "U.S. Meat Farmers Brace for Limits on Antibiotics." Erik Eckholm reports:

"Now, after decades of debate, the Food and Drug Administration appears poised to issue its strongest guidelines on animal antibiotics yet, intended to reduce what it calls a clear risk to human health. They would end farm uses of the drugs simply to promote faster animal growth and call for tighter oversight by veterinarians.

The agency’s final version is expected within months, and comes at a time when animal confinement methods, safety monitoring and other aspects of so-called factory farming are also under sharp attack…"

Read the full article.

return to top

ClearWater Conservancy: Restoration in Practice

By Jennifer Chesworth

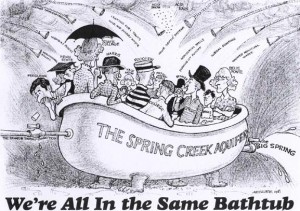

In Central Pennsylvania, a local grassroots organization has made restoration the centerpiece of watershed protection.

The ridges, valleys, farms and forests of Centre County, Pennsylvania share a truly unique “karst” topography of limestone and shale, underground streams, numerous caves, springs, and sinkholes, and a rare outcropping of quartz crystal that cuts across the center of the state. Famous as a destination for fly fishermen (even president Jimmy Carter used to frequent the local waters of Spring Creek), the county sits atop a hydro-geological divide, with most of its watersheds feeding the Susquehanna River and Chesapeake Bay, while some flow across the Allegheny Plateau to join the Ohio River and the Mississippi. The region’s water resources include the second largest spring in the state, Big Spring in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, which flows at 14 and a half million gallons per day, supplying water to a Coca-Cola bottling plant, among other users. Farming, especially dairy farming, is still the traditional way of life in the mostly rural areas of Centre and surrounding Counties.

The ridges, valleys, farms and forests of Centre County, Pennsylvania share a truly unique “karst” topography of limestone and shale, underground streams, numerous caves, springs, and sinkholes, and a rare outcropping of quartz crystal that cuts across the center of the state. Famous as a destination for fly fishermen (even president Jimmy Carter used to frequent the local waters of Spring Creek), the county sits atop a hydro-geological divide, with most of its watersheds feeding the Susquehanna River and Chesapeake Bay, while some flow across the Allegheny Plateau to join the Ohio River and the Mississippi. The region’s water resources include the second largest spring in the state, Big Spring in Bellefonte, Pennsylvania, which flows at 14 and a half million gallons per day, supplying water to a Coca-Cola bottling plant, among other users. Farming, especially dairy farming, is still the traditional way of life in the mostly rural areas of Centre and surrounding Counties.

The karst topography of the region means that the ground is very porous, with groundwater that’s especially  susceptible to contamination from surface activities, impacting the quality of water far beyond the boundaries of county lines and jurisdictions.

susceptible to contamination from surface activities, impacting the quality of water far beyond the boundaries of county lines and jurisdictions.

That’s why ClearWater Conservancy, a regional land trust and natural resource conservation organization founded in 1980, has built a strong network of local volunteers and landowners working to restore critical, natural buffers that protect local springs, streams, and groundwater resources. With dozens of riparian restoration projects already under its belt and about 10 local property owners contacting the organization each year to participate in the restoration program, ClearWater’s success — and the long-term effectiveness of restoration — has depended to a great extent on keeping local volunteers engaged and glad to be involved.

Annual events, such as the Watershed Clean-up Day held every spring to honor Earth Day, the Spring Creek Clean-up Day each autumn, and the locally-popular winter fundraiser “For the Love of Art and Chocolate,” help reinforce friendships among volunteers and sustain enthusiasm in the broader community. Who doesn’t love chocolate?

Annual events, such as the Watershed Clean-up Day held every spring to honor Earth Day, the Spring Creek Clean-up Day each autumn, and the locally-popular winter fundraiser “For the Love of Art and Chocolate,” help reinforce friendships among volunteers and sustain enthusiasm in the broader community. Who doesn’t love chocolate?

“We’ve learned a lot over time,” says Katie Ombalski, a conservation biologist who has worked at the organization for ten years, one of five staff members at ClearWater. “Outreach is important, but you’ve also got to carefully select appropriate tasks so you have happy volunteers who successfully complete the work.”

“We’ve learned a lot over time,” says Katie Ombalski, a conservation biologist who has worked at the organization for ten years, one of five staff members at ClearWater. “Outreach is important, but you’ve also got to carefully select appropriate tasks so you have happy volunteers who successfully complete the work.”

Much of the work that goes into restoration — preparing ground for planting trees, moving rock, picking appliances that may have been there for 50 years out of a sinkhole — is hard labor.

“A riparian restoration site will need regular maintenance for 3 to 5 years, until tree seedlings can establish a strong enough root ball. People may show up for a day of hard labor, but if they go home tired and sore, they justifiably feel like they’ve made a significant contribution. We’ve learned that they’re not as likely to show up for on-going work parties,” Katie explains. “Now we use contractors to come in and prepare the sites and plant large numbers of trees and shrubs. Jobs like small tree planting and installing tree tubes are better suited for most volunteers.”

“A riparian restoration site will need regular maintenance for 3 to 5 years, until tree seedlings can establish a strong enough root ball. People may show up for a day of hard labor, but if they go home tired and sore, they justifiably feel like they’ve made a significant contribution. We’ve learned that they’re not as likely to show up for on-going work parties,” Katie explains. “Now we use contractors to come in and prepare the sites and plant large numbers of trees and shrubs. Jobs like small tree planting and installing tree tubes are better suited for most volunteers.”

Site preparation conducted by contractors, usually professional arborists, typically begins with application of a glyphosate herbicide and pre-emergence treatments. But in the case of ClearWater’s largest and most successful project, restoration of a riparian strip nearly 3/4 of a mile long on an agricultural property long-used as a sheep farm owned by Penn State University, chemical applications were not an option. The site is within close proximity to a wellhead used as the university’s drinking water supply. As property owner, the university chose to apply a zero-risk policy rather than chemical treatments.

“Preparing the site was done entirely by hand, which was extremely difficult as we found those agricultural grasses are incredibly thick-rooted and tenacious,” says Katie. “We could not have accomplished all that prep work and hand-weeding maintenance in subsequent years on such a large site without the university as landowner. The university has a farm manager and staff who are regularly able to contribute time to the Sheep Farm Restoration Project.”

With $25,000 in private funding from the Foundation for Pennsylvania Watersheds, ClearWater partnered with the university and with the local Spring Creek Chapter of Trout Unlimited to improve in-stream habitat and to plant and maintain a riparian buffer along the creek on the Sheep Farm. Stream-side fencing to keep the sheep from walking into the creek bed was moved away from the bank on both sides of the stream, back into the pasture to an average 52 feet width. Chemical-free site preparation included using a mower deck with a tiller to clear an 8 by 8 feet area for every tree to be planted, and auguring 24 inch holes at each point to completely remove all of the root mass from grasses before planting trees. After planting, black plastic weed barriers covered the ground around each tree, along with hardwood mulch brought in from the university’s composting facility. Mulch was spread 4 inches thick on the entire 8 by 8 feet area for every tree. Grasses and other weeds, if left in the ground, can easily out-compete tree seedlings for water. As part of regular, ongoing maintenance, volunteers go in each year and hand-weed, shore up the protective tubes around the seedlings, and reapply mulch.

With $25,000 in private funding from the Foundation for Pennsylvania Watersheds, ClearWater partnered with the university and with the local Spring Creek Chapter of Trout Unlimited to improve in-stream habitat and to plant and maintain a riparian buffer along the creek on the Sheep Farm. Stream-side fencing to keep the sheep from walking into the creek bed was moved away from the bank on both sides of the stream, back into the pasture to an average 52 feet width. Chemical-free site preparation included using a mower deck with a tiller to clear an 8 by 8 feet area for every tree to be planted, and auguring 24 inch holes at each point to completely remove all of the root mass from grasses before planting trees. After planting, black plastic weed barriers covered the ground around each tree, along with hardwood mulch brought in from the university’s composting facility. Mulch was spread 4 inches thick on the entire 8 by 8 feet area for every tree. Grasses and other weeds, if left in the ground, can easily out-compete tree seedlings for water. As part of regular, ongoing maintenance, volunteers go in each year and hand-weed, shore up the protective tubes around the seedlings, and reapply mulch.

“We even had two Eagle Scouts who earned their wings by participating in the Sheep Farm Restoration Project,” says Katie. “They helped with planning, ordering, and volunteer coordination, as well as pitching in on work days. The project required a lot of administrative work. It was a good education for them, and something fun that they’ll never forget.”

Partnerships have been as critical to ClearWater’s success as is its ability to retain volunteers. When a local farm property adjacent to state forest lands recently became  available, ClearWater stepped in to purchase the farm from a private developer and placed it in trust, then transferred the property to the Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry. The transfer increased Rothrock State Forest by 423 acres. Called Musser Gap, the site includes an old dam and reservoir that at one time supplied water to the university, several miles away. This month, with the help of the Spring Creek Chapter of Trout Unlimited and Pennsylvania DCNR’s Bureau of Forestry, ClearWater is initiating a new project to remove the dam and restore the natural stream bed through the gap.

available, ClearWater stepped in to purchase the farm from a private developer and placed it in trust, then transferred the property to the Pennsylvania Bureau of Forestry. The transfer increased Rothrock State Forest by 423 acres. Called Musser Gap, the site includes an old dam and reservoir that at one time supplied water to the university, several miles away. This month, with the help of the Spring Creek Chapter of Trout Unlimited and Pennsylvania DCNR’s Bureau of Forestry, ClearWater is initiating a new project to remove the dam and restore the natural stream bed through the gap.

“The dam no longer has any functional use and is in a tremendous state of disrepair,” says Katie. “Now that it’s no longer private property and the public can access the dam area, it’s a real liability. Musser Gap is a popular hiking destination and home to  one of five remaining Brook Trout populations in our region, so people do go up there. Restoring the stream bed is a good idea any way you look at it.”

one of five remaining Brook Trout populations in our region, so people do go up there. Restoring the stream bed is a good idea any way you look at it.”

Hauling and removing stone and concrete from the site would damage the forest on the way down the gap and out. Fortunately, concrete on the dam’s large walled basin was applied like plaster, with native stones underneath. The walls will be broken apart and used to fill in the basin, then covered with as much additional native stone as needed, with stepped pools built above the dam for grade control and amphibian habitat.

With so many local landowners turning to ClearWater for help and advice on restoring native habitat and protecting the watershed, the organization decided it was important to set a good example. Its own offices, in what was once a Township municipal building still owned by the local government, are located in what Katie calls “a sea of asphalt.” With the help of their landlord, Patton Township, and with volunteer Master

With so many local landowners turning to ClearWater for help and advice on restoring native habitat and protecting the watershed, the organization decided it was important to set a good example. Its own offices, in what was once a Township municipal building still owned by the local government, are located in what Katie calls “a sea of asphalt.” With the help of their landlord, Patton Township, and with volunteer Master  Gardeners who keep an eye on the place, ClearWater installed rain barrels and a rain garden, widened planting space, reduced impervious surface further still by getting rid of one driveway altogether, and created a native meadow including plants to draw birds and butterflies. Interpretive panels explain landscaping choices to visitors, with the site serving as a demonstration for ClearWater’s educational “Watershed-Wise Techniques for Backyards and Businesses” program. The building is pictured here before and after installation of the rain garden.

Gardeners who keep an eye on the place, ClearWater installed rain barrels and a rain garden, widened planting space, reduced impervious surface further still by getting rid of one driveway altogether, and created a native meadow including plants to draw birds and butterflies. Interpretive panels explain landscaping choices to visitors, with the site serving as a demonstration for ClearWater’s educational “Watershed-Wise Techniques for Backyards and Businesses” program. The building is pictured here before and after installation of the rain garden.

“It’s hard to tell people what to do when they can see you’re not doing it yourself,” says Katie. “We wanted to give people ideas, and to show that you can do all this at home, even on less than a half-acre.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * *

The good people of ClearWater Conservancy can be reached at (814) 237-0400 and found on the web here.

“We’re All in the Same Bathtub” copyright Jim McClure, all rights reserved for ClearWater Conservancy.

Jennifer Chesworth is editor of Ecological Landscaping Association’s e-news and is a native Central Pennsylvanian.

Posted: September 14th, 2010 under Chemical Pesticides and Herbicides, Ecological Maintenance, Green Spaces — Public, Meadows, Restoration, Trees, Volunteer Workers, Water Quality, Weeds and Weeding, Wildlife Habitats.

return to top

"A Bang for Your Buck in the Berkshires."

Yankee Magazine Sept.-Oct. 2010

WANT TO ENCOURAGE THE LOCAL ECONOMY? TRY PRINTING YOUR OWN REGIONAL MONEY.

In Great Barrington, Massachusetts, I gave the nice man in the Mr. Ding a

Ling truck a W.E.B. Du Bois for my fudgesicle, and he gave me four Mohicans

back in change. I walked over to the food co-op and broke a 50 the one

with Norman Rockwell on the face and my excellent sandwich came with four

Robyn Van Ens in change. If I hadn’t been so hungry, I could have spent my

BerkShares on Web-site design, some septic work, a game of billiards,

snowplowing, or a horseback-riding lesson. Hell, if the horse got sick, I

could have taken her to the vet. But I was still hungry, so I wandered north

to Stockbridge and headed over to the tavern at the Red Lion Inn, the

quintessential Berkshires hostelry. And there I found waiting for me a nice

glass of Berkshire Blonde ale and a burger, only a Melville all together.

Also waiting was Susan Witt, the force behind America’s most successful

alternative currency. "Oh," she said when I told her about my day, "the

midwife takes BerkShares, and so does the undertaker. You can get a will

done; you can build an addition to your home, fix your car. I like shoes,"

she added, wiggling her toes. "These weren’t cheap."

Money, when you think about it, is hard to explain. Where it comes from, who

decides how much is in circulation, where you get a spare trillion to bail

out your banking system it’s all kind of mysterious. How can I take paper

out of my wallet and use it to persuade someone in China to make me

something? But most of the time we don’t think much about it, any more than

we ponder the mysteries of gravity. If gravity stopped working from time to

time, however, we might start wondering a little more which may explain

why the BerkShares Web site (Berkshares.org) got 3.5 million hits in the

year after our financial crisis erupted.

In fact, the regional currency for Massachusetts’ westernmost county is just

the most prominent of many experiments with money now taking place across

New England, from New Haven, Connecticut, to Portland, Maine, to the entire

state of Vermont. None of these schemes aims to supplant the greenback, but

all try to mend some of its very real defects and to serve as a laboratory

for what comes next. Call it "Currency 3.0": lean, local and maybe very

logical indeed.

Not that the idea is brand-new just the opposite. Some of the first money

that circulated around New England was local: Next door to the Red Lion Inn

is a Berkshire Bank branch; the building’s original occupant, the Housatonic

Bank, printed its own money in the 1800s. You can still see some of those

notes hanging on the wall.

But as the nation prospered and consolidated, the federal currency became

the thing we meant when we said "money." It’s always come with drawbacks,

however: the bust-and-boom cycle, for instance, that saw many communities

issuing scrip during the Depression. Beyond that, the sheer power of money

the fact that you can use it to command someone in China to do something for

you can create problems just as it solves them: the folks in China, or at

Walmart headquarters in Arkansas, may take away the jobs your community

depends on, for instance. Through the 20th century, as consumers transacted

more and more of their business at a distance, local food systems waned; the

big-box stores reduced the civic engagement that came with Main Street.

It’s probably no wonder, then, that the impetus for BerkShares came from the

E.F. Schumacher Society, a Great Barrington foundation formed to promote the

legacy of the British author of "Small is Beautiful". The Berkshires were an

early hotbed of the local-food movement: Robyn Van En, whose face graces the

10 BerkShare note, founded one of the first two CSA (community-supported agriculture) projects in the country in the mid-1980s at her Indian Line

Farm in South Egremont. When the famous economic historian Jane Jacobs

called for regional currencies in a talk in 1983 at the Society’s annual

meeting, her plea fell on receptive ears.

"We’d started with a microloan program [in 1982]," Witt explains. "We got

people to open savings accounts at local banks and pooled that money to

collateralize loans for useful things. Mostly they went to women, and for

products that weren’t really understood by traditional bankers." Then a

favorite local deli came looking for money so it could move. "We said, No,

you have your customers; borrow from them." And thus was born "Deli

Dollars," which let people loan money that could be redeemed in pastrami,

say, once the expansion was complete.

"It got huge press," Witt says. "People were really interested." The local

Chamber of Commerce asked the Schumacher Society to help with a summertime

promotion: Whenever shoppers spent $10 at any of 70 local stores, they got a

$1 certificate that they could redeem over three days in September. "People

came all the way back from Cape Cod to spent $20 worth of these

certificates," Witt recalls. "Merchants loved it. And since we had an Excel

spreadsheet going, they could see how interconnected they actually were."

The leap from gift certificate to currency came in the fall of 2006, when

several community banks offered to issue the money. "You have to remember,"

Witt says, "local bankers are just local guys, their customers are local

businesses; they’re thinking of what will work for these local businesses.

They’ll stretch for them."

Here’s how it works: You walk into any branch of the five banks that offer

the notes and hand the teller $95 in U.S. dollars. She hands you 100

BerkShares. You spend them at the deli, the bar, or the bookstore. The bar

owner then takes her BerkShares from the till and spends them at the deli,

the bookstore, or Jakob Kent Jewelry. Or, if she has to pay for something

that nobody local is producing, she takes her BerkShares back to the bank

and reconverts them into dollars, at the same 95 percent exchange rate.

Some people get paid partly in BerkShares; some towns are considering taking

them for certain fees and taxes. It’s not an experiment anymore: The

2.5-millionth BerkShare went into circulation last fall.

It’s also not the only new approach to money under way in New England. In

Greater New Haven, for instance, SHARE Haven Time Bank is busy converting

spare hours into spending power. You offer something you’re good at; at

press time, the Web site listed a variety of services, from cat sitting to

architectural design. If you spend an hour helping someone in the network,

you’ve earned an hour of someone else’s time; you can get someone to shovel

your drive, or give you a massage afterwards.

Hour Exchange Portland is larger and more established. Current projects

include making sure the homes of all 600 active members get weatherized with

the donated labor the network can mobilize; you get spray foam insulation,

caulking, and weatherstripping, and you pay it back to the system in baking,

or midwifery, or whatever it is you do.

Time-dollar programs derive from old-fashioned bartering, of course, but

with an egalitarian twist: every hour is worth the same thing. Portland’s

credo states it simply: "Everyone has value, everyone’s time is equal,

everyone has something to offer. The real economy is people. We value work.

We value the work it takes to make healthy children, a healthy community, a

sustainable future." It sounds positively Scandinavian.

If you’re a little more hard-nosed, then consider the new Marketplace

program launched this past spring by Vermont Businesses for Social

Responsibility and Vermont Sustainable Exchange. It’s kind of like barter,

too, but highly computerized, and filled with excitingly business-like

buzzwords. "We think of it as a recession beater a cash-flow management

tool," says VBSR executive director Will Patten. "Every business has extra

capacity, or products it’s overstocked on," he explains. "Everyone has extra

capacity." Now other member businesses can buy that extra capacity with

their own excess, no money involved.

"Say I need to buy some compost," says Will Raap, who often needs to buy

compost because he’s the founder and chairman of Gardener’s Supply Company,

an enormous mail-order house based in Burlington. "I may be short of cash,

and the compost guy may have a glut at the moment. So I can transact that in

the online exchange system, and the compost company can take the credits I

gave it and use them to buy fuel for the truck to load the compost onto. The

fuel company says, ‘I need accounting services,’ and finds someone in the

network to provide them."

It works like money, but it lets you pay for what you have too little of

(fuel) with what you have too much of (compost). If you had to barter point

by point, not only would you have to find a fuel dealer who needed compost,

but you’d have to find him at just the moment when he also had extra fuel he

needed to get rid of. "Barter requires the incidence of coincidence," says

VSE founder Amy Kirschner, who runs the Marketplace software under a license

from the Scottish inventors. "Instead, we’re a little bit Amazon, a little

bit Craigslist, a little bit eBay."

Kirschner started work on Marketplace’s business-to-business electronic

exchange after her attempt to start a BerkShares-like local currency in

Burlington had foundered. "Having a piece of paper go around is a bit of a

logistical nightmare," she says. "Burlington Bread didn’t fit into

cash-register drawers, it was hard to make change, employees weren’t trained

to deal with it." She’s happier with the electronic model, in part because

she’s dealing directly with businesses that are used to thinking in hard

economic terms.

"We finally nailed the economic argument it’s spare capacity," she adds."Would you rather pay a bill with a gift certificate to your business or

with cash? There’s already trust within our network of businesses; these are

the kinds of people who want to work with one another."

Susan Witt wouldn’t argue with any of those logistical challenges, but for

her they’re part of the rationale for BerkShares: The currency is literally

teaching people to think more carefully about how their habits build or

erode community. It’s about creating trust in a world where economists have

taught us that we’re self-interested individuals and nothing more. "I’ll be

in line behind someone at a store, someone who’s supported us," she says."And yet she’s whipping out a credit card to pay. I ask her, ‘Where are your

BerkShares?’ And she’ll say, ‘It’s inconvenient. And I get airline miles

with this card.’ We’re so entranced by the ease of this economic exchange."

Witt wrote recently about another local woman, someone who had called her

office to ask how to make a donation to a local nonprofit in BerkShares. She

couldn’t just write a check, Witt explained to her. She’d need to "walk or

drive to the project’s office, call the staff together, look them directly

in the eye, tell them how important their work is to the community, and hand

them an envelope with a big stack of BerkShares."

Those bank notes would be nice, but so would the sentiment; in the end, it’s

entirely about building community, and so the connection counts as much as

the money. Here’s Jasmine Stine, an intern at the Schumacher Society: "My

housemate was in line at Guido’s [an upscale produce market in Great

Barrington], right in between two other people who were paying in

BerkShares. It turns out that one guy was making biodiesel, and the other

guy needed some. That’s the kind of conversation we’ve got to start having."

The Schumacher Society which is now combining forces with England’s New

Economics Foundation, another booster of local currencies sees lots of

room for BerkShares to grow. The currency is now spreading out of the

southern half of the county the Tanglewood Berkshires into the grittier

Pittsfield area, and even to a few towns just over the New York and

Connecticut state lines. And the Society is also trying to figure out how to

start making loans in the local currency, not tied to federal dollars, which

would mean backing the BerkShares with something real. Not gold, but a

basket of commodities firewood, apples, wind power the kinds of things

you can produce in Western Massachusetts, where gold mines are scarce.

The loans would be designed to build local economic power: to capitalize the

factories and workshops that could bring production and jobs back home. That

could reduce the scale of the sprawling global economy at least a little

and trim the danger of the next crash a little, too. I’m betting a Melville.

return to top

How to shrink a city

Not every great metropolis is going to make a comeback. Planners consider some radical ways to embrace decline.

By Drake Bennett, The Boston Globe | September 5, 2010

Since cities first got big enough to require urban planning, its practitioners have focused on growth. From imperial Rome to 19th-century Paris and Chicago and up through modern-day Beijing, the duty of city planners and administrators has been to impose order as people flowed in, buildings rose up, and the city limits extended outward into the

hinterlands.

But cities don’t always grow. Sometimes they shrink, and sometimes they shrink drastically. Over the last 50 years, the city of Detroit has lost more than half its population. So has Cleveland . They’re not alone: Eight of the 10 largest cities in the United States in 1950, including Boston , have since lost at least 20 percent of their population. But while Boston has recouped some of that loss in recent years and made itself into the anchor of a thriving white-collar economy, the far more drastic losses of cities like Detroit or Youngstown , Ohio , or Flint , Mich. – losses of people, jobs, money, and social ties – show no signs of turning around. The housing crisis has only accelerated the process.

Now a few planners and politicians are starting to try something new: embracing shrinking. Frankly admitting that these cities are not going to return to their former population size anytime soon, planners and activists and officials are starting to talk about what it might mean to shrink well. After decades of worrying about smart growth, they’re starting to think about smart shrinking, about how to create cities that are healthier because they are smaller. Losing size, in this line of thought, isn’t just a byproduct of economic malaise, but a strategy.

The resulting cities may need to look and feel very different – different, perhaps, from the common understanding of what a modern American city is. Rather than trying to lure back residents or entice businesses to build on vacant lots, cities may be better off finding totally new uses for land: large-scale urban farms, or wind turbines or geothermal wells, or letting large patches revert to nature. Instead of merely tolerating the artist communities that often spring up in marginal neighborhoods, cities might actively encourage them to colonize and reshape whole swaths of the urban landscape. Or they might consider selling off portions to private companies to manage.

A few of these ideas are actually starting to be tried. In Detroit, a city that now has more than 40 square miles of vacant land, Mayor Dave Bing has committed himself to finding a way to move more of the city’s residents into its remaining vibrant neighborhoods and figuring out something else to do with what remains. A growing number of cities and counties are creating "land banks" to enable them to clear the administrative hurdles that previously prevented them from taking control of blighted blocks of abandoned homes.

The idea remains controversial. Mayor Bing’s proposal has been fiercely criticized in Detroit, and some planners – along with many of the residents of blighted neighborhoods – argue that planned shrinkage is simply an excuse to stop helping the people in the worst-hit neighborhoods, and will only compound the pain that industrial decline and the housing collapse have had on the lives of poor and working-class residents.

But to the proponents of the idea, it’s a recognition of reality, and, more than that, an opportunity to free struggling cities from a paralyzing preoccupation with past glories. At its most ambitious, smart shrinking offers an opportunity to rethink what makes a city a city: Some planners envision a landscape that isn’t recognizably urban, suburban, or rural, but some combination of the three, with multistory apartment buildings next to working farms, and public transit lines extending through neighborhoods where most households have ample space to park their cars.

"This is an area where five years ago basically nobody except a couple of academics and oddball planners were talking about it, and now it’s pretty widely accepted. You’ve got just a lot of land and a lot of buildings for which there is no quote redevelopment potential," says Alan Mallach, an urban planning expert at the Brookings Institution. "Part of what you have to do is think about ways to use land that help improve the quality of life but don’t involve actual building."

The golden age of growth for the American city stretched from the late 1800s into the early 1900s. As immigrants from rural America and abroad flooded in, cities expanded outward, annexing more and more of the surrounding land. By the 1920s, however, suburbs in many parts of the country began to incorporate and to assert home rule, hemming cities in. At the same time, the middle class began to migrate to the suburbs, leaving the cities to the poor. That meant less tax revenue and higher social services costs, and the process of outmigration fed on itself. As the manufacturing industries that had driven the original growth moved abroad or died out in the decades after World War II, cities from St. Louis to Chicago to Baltimore stopped growing in population and began to dwindle.

Some forms of shrinking are more destructive than others. In Boston, for example, much of the population loss came from a reduction in family size, with the number of households remaining roughly the same. In Detroit and Cleveland, however, the decline left large portions of the city barely populated at all. And the recent nationwide collapse in housing prices has only exacerbated the trend, taking a process that had been occurring gradually and sharply accelerating it.

"For the first time, places like Detroit and Youngstown are realizing that they are not going to regain the population that they lost," says Daniel D’Oca, an urban planner and partner at the planning and architecture firm Interboro Partners who has studied Detroit ‘s abandoned lot problem.

Cities like Detroit have suffered from a collapse in tax revenue. They have to deal with block upon block of buildings that have been left to the elements and a frayed urban fabric where the last holdouts from once-bustling neighborhoods now are isolated among vacant homes and lots. As a result, simply providing basic services like garbage collection, electricity, policing, and firefighting becomes more expensive and more difficult. Today whole sections of Detroit and Cleveland and Youngstown look like ghost towns: boarded-up houses everywhere, boarded-up office buildings, schools, even hospitals and train stations alongside vacant lots, with wild animals creeping back in.

But though the trend is decades old, urban planners have only recently begun to think about shrinking not as a setback on the path to future growth but as a condition to be actively managed. It’s a radical shift.

"It’s so contrary to what most planners do, it’s contrary to what we spend our time teaching students, [which is] all about how do you manage growth and accommodate growth," says Joseph Schilling, who teaches urban affairs and planning at Virginia

Tech University and helped launch the National Vacant Properties Campaign. "The challenge for planning is how do you adapt existing tools and planning strategies to deal with an economy and market that is either totally dysfunctional or will have maybe slow, modest growth at best."

Part of the difficulty planners face in thinking about the problem is that there are no real case studies of managed urban shrinking in the United States. There is, however, some precedent abroad. After the collapse of the Berlin Wall and reunification of Germany, the former East Germany experienced a massive emptying, with waves of residents from cities like Leipzig , Dresden , and Jena leaving for the more prosperous west.

Leipzig ‘s government in particular realized its diminished size would be a permanent condition and responded accordingly. According to Tamar Shapiro, the director of the comparative domestic policy program at the German Marshall Fund, city officials set out to address the problems created by all of the empty homes abandoned by those who had left. Unmaintained, they were an eyesore, and as they fell apart, a danger. They dragged down the value of the surrounding properties and left hollowed-out neighborhoods that attracted squatters and crime.

But since eminent domain was all but unheard of in Germany and the city couldn’t afford to buy out the remaining landowners in the largely abandoned neighborhoods, officials came up with something else, a new kind of land-use contract in which private owners signed over control to the city for a period of several years in exchange for not having to pay property taxes. The government was free to do what it wanted with the space – which was usually tearing down the buildings to create parks and other green spaces – and if the city’s population were to begin to grow again, the owner would be able to develop the land again when the contract ended.

Planners and city and state officials are beginning to look at similar ideas here in the United States. Detroit, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and several other cities have multiple nonprofits dedicated to turning vacant lots and blocks into parks. Many of the plots are tended in some way, some are left to return to nature, perhaps with a trail or two through them. The aim is partly aesthetic, but also an attempt to increase the value of neighboring homes and neighborhoods by replacing vacant houses or other signs of blight with greenery.

Other organizations are looking to turn vacant lots to more straightforwardly productive uses. Urban farms, for example, are spreading in several cities. These are not just community gardens, but larger-scale operations meant to be viable commercial enterprises. One of the most successful is the Ohio City Farm, a 6-acre plot behind a large housing development across the Cuyahoga River from downtown Cleveland. The farm, still in its first growing season, produces over 100 varieties of heirloom fruits and vegetables, and is worked by a few young entrepreneur farmers, residents of the housing development, and, thanks to a local nonprofit, refugees who have resettled in the area.

The abundance of vacant land is also providing a better way to deal with storm water runoff, a serious problem for large cities. Because rainwater and sewage typically flow into the same pipes, large storms overload urban sewage systems, causing raw sewage to be dumped into surrounding waterways. Soil, of course, absorbs water much better than concrete. Cleveland and Philadelphia are now dotted with vacant lots that have been landscaped into so-called bioswales, patches of land with a slight gradient, loose soil, and vegetation, that collect storm water and filter out the pollutants it picks up as it flows over city streets – relieving some of the pressure on the sewage system.

Some areas are being targeted as sites for green energy production. Lackawanna, N.Y., a former steel town just south of Buffalo, has a wind farm built over the ruins of a decrepit Bethlehem Steel <http://finance.boston.com/boston?Page=QUOTE&Ticker=BHMMQ>

plant. Terry Schwarz, a planner who heads the Cleveland Urban Design Collaborative and has worked extensively with the city to repurpose vacant lots, believes that some of the land could make good sites for land-intensive energy sources like solar cells, or for geothermal wells to power adjacent buildings.

Schwarz’s larger vision is of a city with a reduced ecological footprint.

"We’re trying to take advantage of this moment to put a more sustainable pattern of urban development in place," she says. "We want to delineate parts of the city where development probably shouldn’t have occurred in the first place." One idea she and others are pushing is opening up the many creeks paved over during the construction of Cleveland. Doing so would leave the city braided with waterways, making it more pleasant and restoring a more natural water flow into the Cuyahoga River.

Schwarz and other planners involved in these efforts argue that some of the lessons they’re learning about how to use open land as a form of green infrastructure could apply in cities that aren’t facing the same population decline.

"How you unearth a creek in the city, how you separate storm water and sanitation water, it’s part of thinking more productively about landscapes, about a more ecological urban form," says Dan Pitera, an architect at the University of Detroit Mercy.

All of these proposals, of course, merely shrink a city’s supply of inhabited land. Edward Glaeser, an urban economist at Harvard, argues that cities like Detroit might think of shrinking in a more fundamental way, selling off parts of the city to private entities. Those companies would then manage their parts of the city the way the holders of private charters governed colonies in the early days of North American settlement. Glaeser concedes that the idea is politically improbable. Still, he points out that recent decades have seen the rise of privately owned and managed housing developments throughout the suburbs – he’s just proposing trying it in the city.

"You could think about the city shrinking not just in terms of the number of occupied homes, but that the city’s own political footprint would shrink, in the same sense that it expanded like crazy in the 19th century," he says.

Shrinking, as a strategy, certainly has its critics, who see it as a continuation of decades of coercive urban renewal strategies. Rather than trying to revitalize dying

neighborhoods, shrinking simply gives up on them. "I’ve yet to be shown a city or a community that has been revived through shrinkage," says Roberta Brandes Gratz, an urban critic and the author of the recently published "Battle for Gotham: New York in the Shadow of Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs."

Proponents of shrinking readily agree that forcing people to move should, whenever possible, be avoided. But the larger issue, they argue, is that talking about shrinking or not shrinking is somewhat beside the point; these cities have already shrunk, and they need to reconcile their new population with a built environment meant for many more people.

It’s a problem even the fastest-growing cities may someday face. "One hundred years ago, Cleveland wouldn’t have expected to be in the situation it is today," Schwarz says, "but all cities grow and all cities decline and I think there are lessons that we can about how to manage decline that apply to all cities."

Drake Bennett is the staff writer for Ideas. E-mail [email protected] <mailto:[email protected]> .